Since 1976, Rogério worked at Varig, then the largest Brazilian airline – and which went bankrupt in 2006. Before discovering HIV, Rogério was part of a solidarity network of Varig employees that helped hundreds of people with the virus while the drugs were not accessible in Brazil. The company’s stewards took prescriptions abroad – mainly to the United States – where they bought or obtained the medicines through donations. Then, they brought drugs to the country on company flights.

Since the commissioners and crew did not need to go through customs, the pills entered Brazil freely – in theory, as they were not registered or marketed in the country, the system was a kind of “smuggling for the good”.

According to former employees, airport workers knew about the import, but, given the seriousness of the epidemic, they let the material pass through customs barriers without problems.

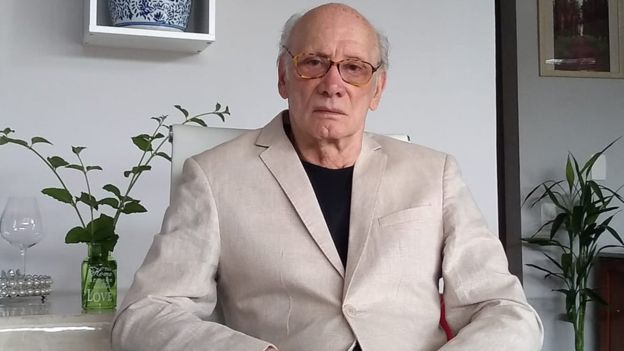

The medicines were then delivered to the company’s headquarters in Rio. “There was even a small window where people picked up the boxes. It was a very competent system: in 48 hours the patient would get the medicine”, says Mario Augusto dos Santos Filho, 78, former head of Varig’s international flight attendants.

According to him, the voluntary and free service lasted from the late 1980s until at least 1996, when Congress approved the law that guarantees universal access to treatment in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS).

‘For solidarity’

The import of pills, however, did not start with AIDS. Before the outbreak of the epidemic in the early 1980s, flight attendants were already using international Varig flights to provide drugs for other diseases, such as cancer.

“Sometimes, the medicine didn’t exist here or cost around US$ 5,000. We bought it cheaper in pharmacies in New York, Paris, Rome, and brought it here. Everything was done out of solidarity, without financial gain”, says Mario Augusto, who, before becoming chief, served for decades as a flight attendant on international flights.

He tells a curious story from that period: “Once, a famous woman, and I’m not going to tell you her name, needed to be tested to confirm that she still had cancer. So she gave me a container with blood samples to take to the United States and, days later, brought the result: she no longer had the disease.”

At that time, Varig employees were also affected by AIDS. According to Mauro Augusto, about 45 commissioners died in a few years, which alarmed the company and workers. On the other hand, there were reports that infected employees were discriminated against and even fired – the company has always denied it. In 1989, groups of activists protested in front of the headquarters in Rio. There is at least one known case in which Varig was ordered by the court to compensate a former worker who was fired for having HIV.

Former Commissioner Alexandre Santos Silva, 61, recalls that he feared losing his job when he discovered he had HIV in February 1992. “I had colleagues who were fired, but obviously the justification was not the virus. The company said the dismissal was for competence issues “, he says.

He says he consulted a lawyer, who instructed him to send a letter to the directors informing him of the situation – if he were fired, he could sue the court on the grounds that he was discriminated against. “I also pasted a poster on the headquarters wall, telling all my colleagues that I had HIV,” he says.

Even so, he was removed from work on the same day and never came back – he continued, however, having access to Varig’s salary and medical services. “There were very good doctors and psychologists at the company. I was treated by them very attentively,” he says. Years later, Alexandre was retired due to disability.

‘Death Sentence’

Those who discovered HIV at that time, in addition to having a “death sentence”, faced prejudices and stigmas. For a long time, AIDS was mistakenly associated with the LGBT community, with the nickname “gay plague”. Alexandre Santos Silva says, for example, that he lost a good part of his friends to prejudice. “Everyone disappeared. My friends were hiding when they saw me on the street. In my building, people left the elevator when I entered,” he says.

Getting treatment was also a very difficult task, because, for some years, there were no drugs to treat this condition – only the evils called “opportunists”, such as diarrhea and infections. Thousands of people contracted the virus, developed the disease and died quickly.

“There was no way to treat it, because the drugs did not exist here. It needed to matter and most people had no money,” says Márcia Rachid, an infectious disease physician and one of the founders of Grupo Pela Vidda, who still works with people with the virus today.” In 1989, when AZT (the first drug that proved effective in the treatment of AIDS) appeared, the Ministry of Health sent very few units to hospitals,” he says.

At Varig, employees decided to bring drugs from abroad to treat sick colleagues. Rogério says that for more than a year he imported supplies for a friend, who later died. “It was a terrible situation. I remember that I had a phone book that had more people dead than alive,” he says.

Outside patients learned about the solidarity network and started to contact the commissioners, says Mario Augusto. “I got the drugs from two pharmacies in Manhattan. Often, pharmacists donated the boxes to us. For years, these two pharmacists helped a lot of people in Brazil,” he says.

Veriano Terto Júnior, vice-president of the Brazilian AIDS Interdisciplinary Association (Abia), summarizes what it meant to be treated at those times. “We tend to forget this story, but people did anything for the drugs. It was a struggle and a matter of life and death,” says he, who has worked with patients since the 1980s.

Mortality and infection

After a few years, Varig’s informal import is no longer necessary. In the mid-1990s, Brazil started to buy medicines, although they were not accessible to everyone. A flood of lawsuits asking SUS to pay for treatment led Congress to pass Law 9,313 in 1996, which guarantees free distribution of medicines.

That year, there was another breakthrough: treatment for HIV / AIDS was focused on when the disease had already developed. However, studies have shown that HIV has no latency – that is, it attacks the body all the time. It was then that the so-called antiretroviral cocktails, a set of drugs that attack the life cycle of the virus, appeared even before the development of the disease. “AZT alone did not work. The treatment started to work when we discovered that it was necessary to associate at least three drugs for the virus”, says infectologist Márcia Rachid.

The public policies of the Brazilian State, which even broke a patent to guarantee the supply of medicines, worked: a recent survey by the Ministry of Health, for example, found that 70% of adults and 87% of children diagnosed between 2003 and 2007 had survival over 12 years. In 1996, before treatment was offered, that time was estimated at five years.

On the other hand, Brazil registered a 21% increase in the number of new infections between 2010 and 2018, according to the Joint UN Program for HIV / AIDS, Unaids. Experts argue that this increase in diagnoses may also have occurred because of the expansion of testing in the country.

For Ricardo Diaz, professor of infectology at the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil’s reaction to the epidemic is a world reference. “Our response was quick and innovative. Treatment by SUS reaches 100% of people who discover the virus, which ends up being a way of prevention, as it prevents it from spreading further. The United States, for example, treats only 50% “he says.

But Diaz cites some bottlenecks. “As the number of infections increases, how do we maintain this access? The bill gets higher, more expensive. Another point is that there is still a greater difficulty in maintaining treatment in the most vulnerable part of the population”, he says.

Márcia Rachid cites the old stigma as a factor that still gets in the way. “There are people who are more vulnerable or vulnerable by others: gays, transvestites, transsexuals. Prejudice, sometimes even from the family, still keeps many people from diagnosis and even treatment,” he says. “When you abandon effective treatment, you are opting for death. So, the main bottleneck of HIV and AIDS in Brazil remains prejudice.”